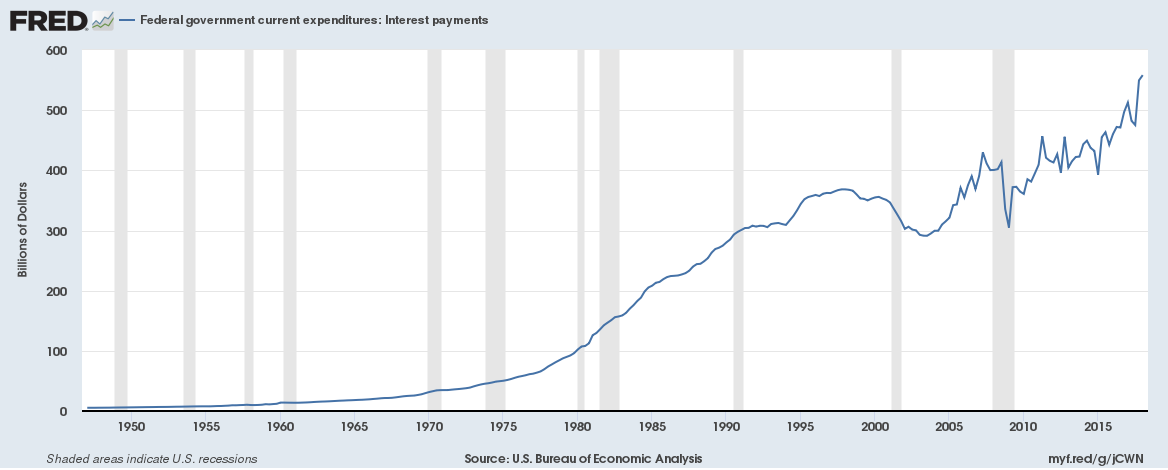

The US government has around $20.5 trillion in debt and pays around $558 billion in interest payments a year (an effective interest rate of 2.72%).

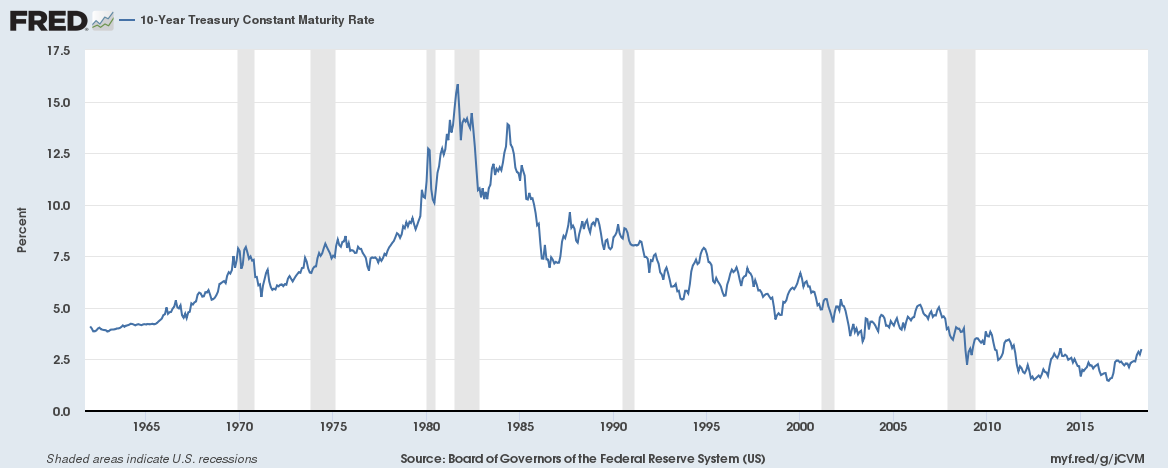

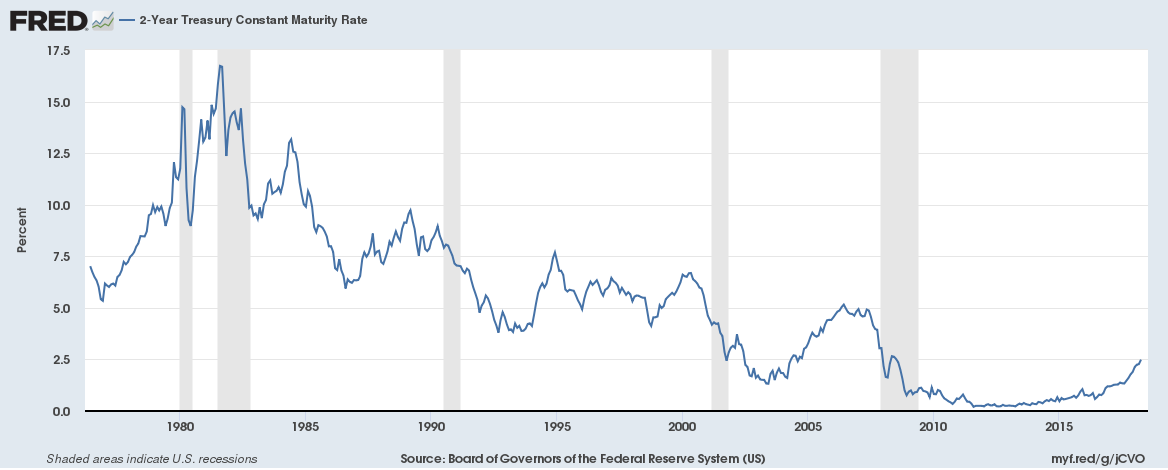

Bond yields have been rising recently in the US on the back of a strong economy. The 10-year bond yield topped 3% (up 0.66% over the past year) recently, the highest since January 2014. The 2-year bond yield topped 2.5% (up a massive 1.18% over the past year), the highest since July 2008 (Read more here).

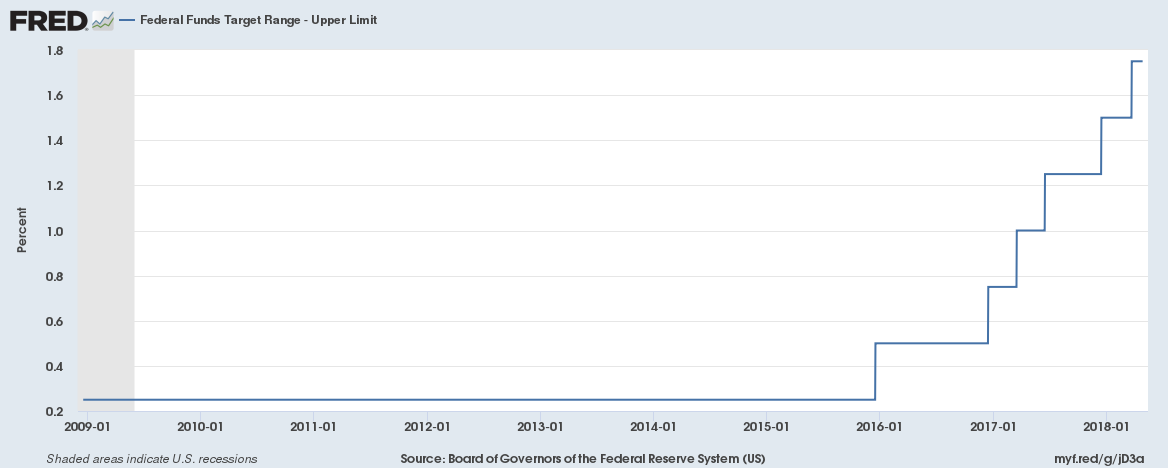

The Federal Reserve under new chairman Jerome Powell approved a 0.25% hike that puts the new benchmark funds rate at a target of 1.5% to 1.75% with expectations that interest rates will rise another 3 to 4 times by the end of the year.

We ask the question whether the US government can really cope with rising bond yields?

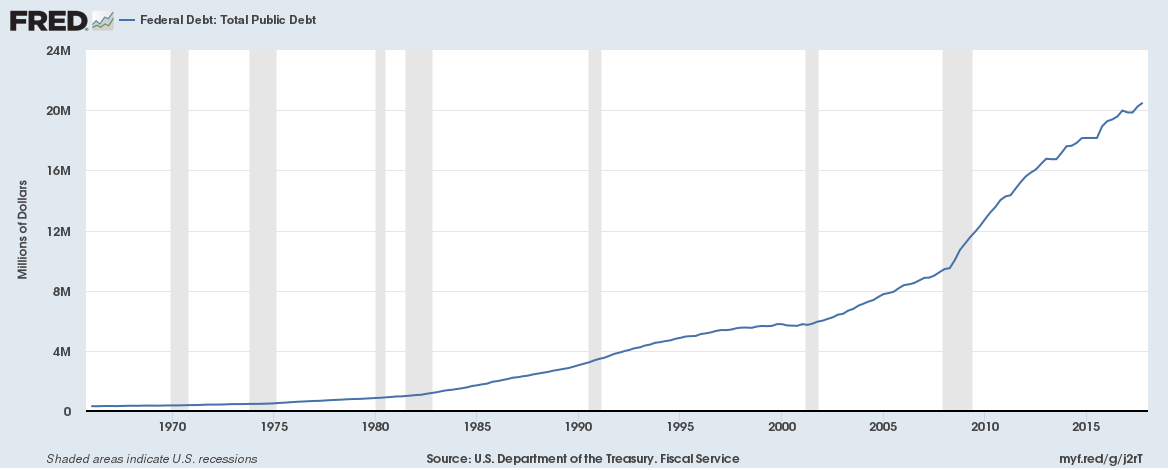

Firstly, Federal government debt has been increasing (see chart below). The US is projected to have a $1 trillion annual fiscal deficit by 2020.

As with rising debt and rising interest rates, expenditure on interest payments has been soaring too (see chart below).

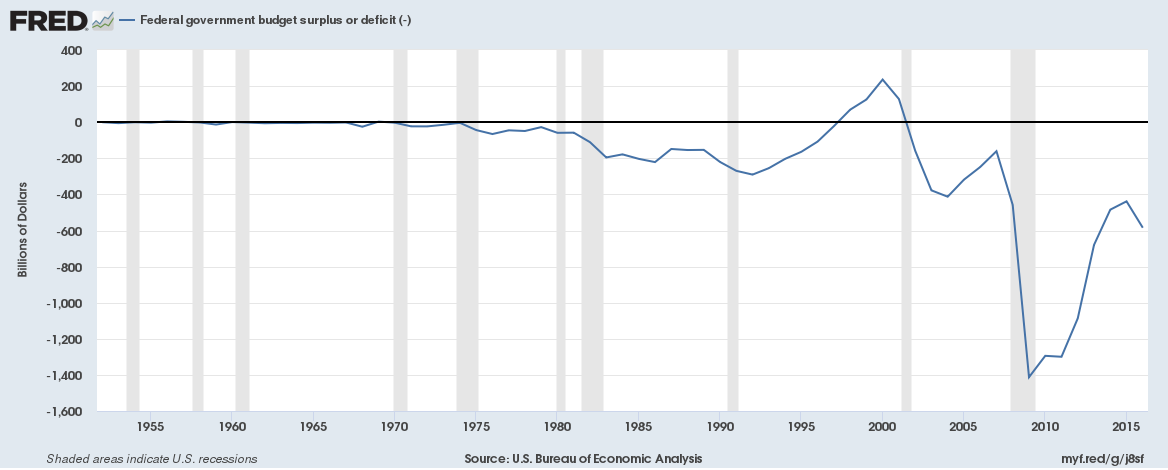

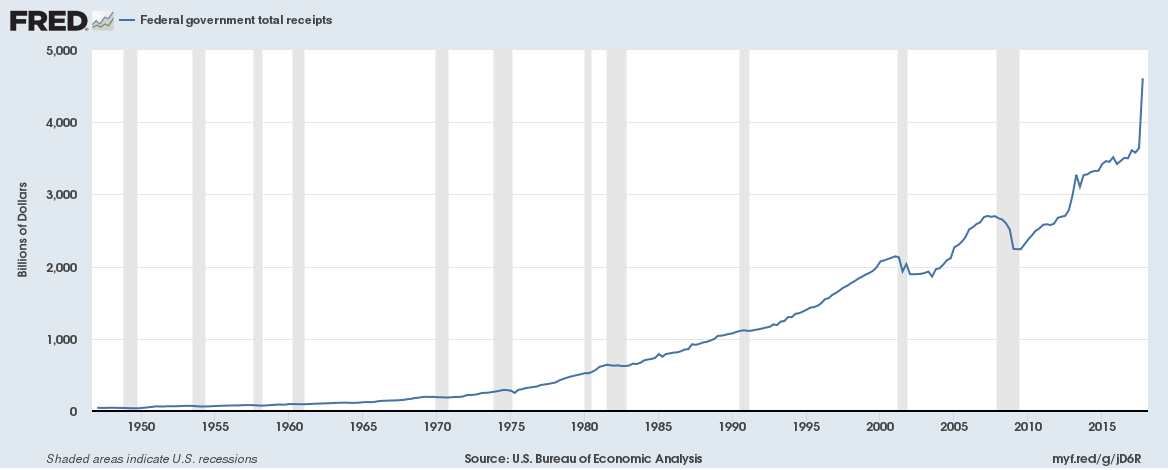

The total federal revenues are around $4.6 trillion (Federal revenue only – state revenues not included) a year, which would mean 12% of all revenues are paid as ongoing interest. The US in unlikely to run a surplus anytime soon, it last ran a fiscal surplus in 2001.

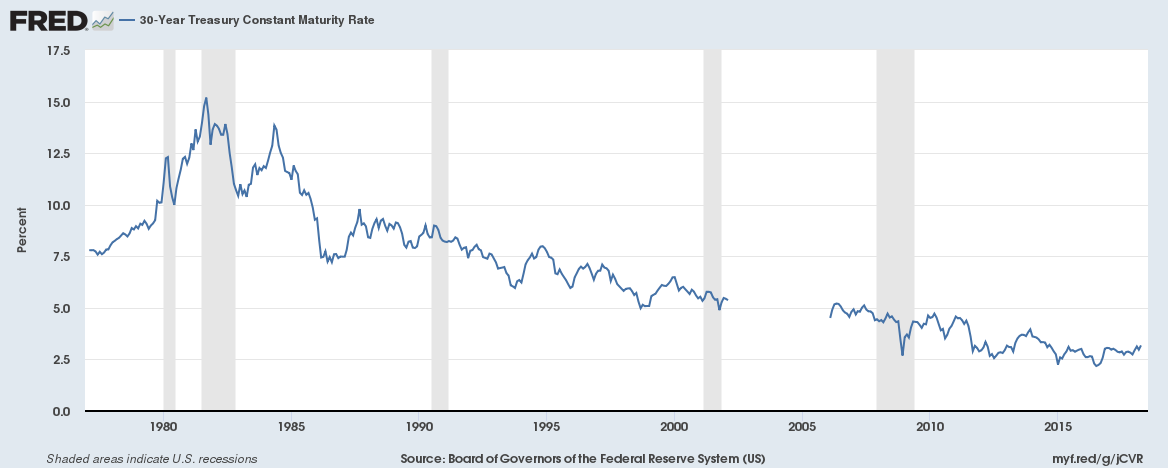

A lot of government borrowing is long term (10-year and 30-year bonds being the most popular) so the impact of rising bond yields won’t be felt immediately.

On an average, around 7% of the total debt is rolled over for the US every year plus new borrowing is made.

A 1% (100 basis points) rise in yields would increase the total interest cost on existing borrowings (new borrowings are not included in this calculation) by 6.3% for the US in the first year (and compounded in future years).

Can the US government manage that? Yes, it can. But let’s not forget bond yields are still historically low (see charts below). Much higher bond yields would spell disaster without a fiscal surplus and falling debt, something that is unlikely to happen anytime soon.