We recently wrote about the impact of rising interest rates for UK households, read more about it here. We also wrote about the impact of higher bond yields for the US government, read more about it here.

Impact of higher interest rates for the UK Government

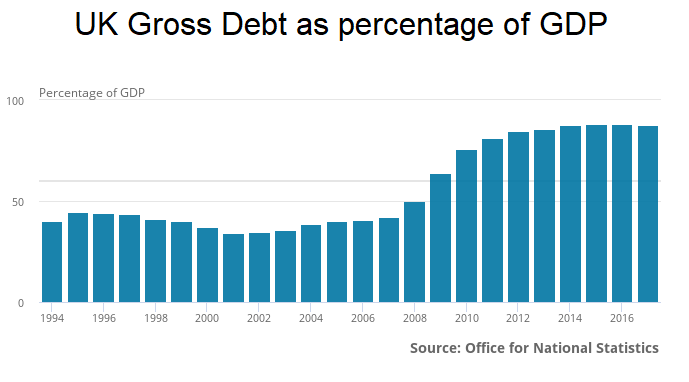

The UK government has around £1.72 trillion in debt and pays around £36 billion in interest payments a year (an effective interest rate of 2%).

The UK tax revenues are around £800 billion a year, which would mean 4.5% of all tax revenues are paid as interest. The UK has paid £540 billion in interest since it last ran a surplus in 2001.

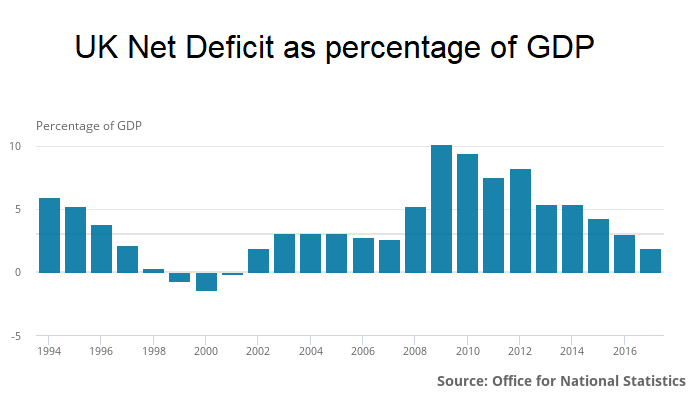

The UK government has projected to balance its books and generate a surplus in 2025. That surplus target year has changed several times and going by past precedence it should be taken with a pinch of salt.

The UK government has projected to balance its books and generate a surplus in 2025. That surplus target year has changed several times and going by past precedence it should be taken with a pinch of salt.

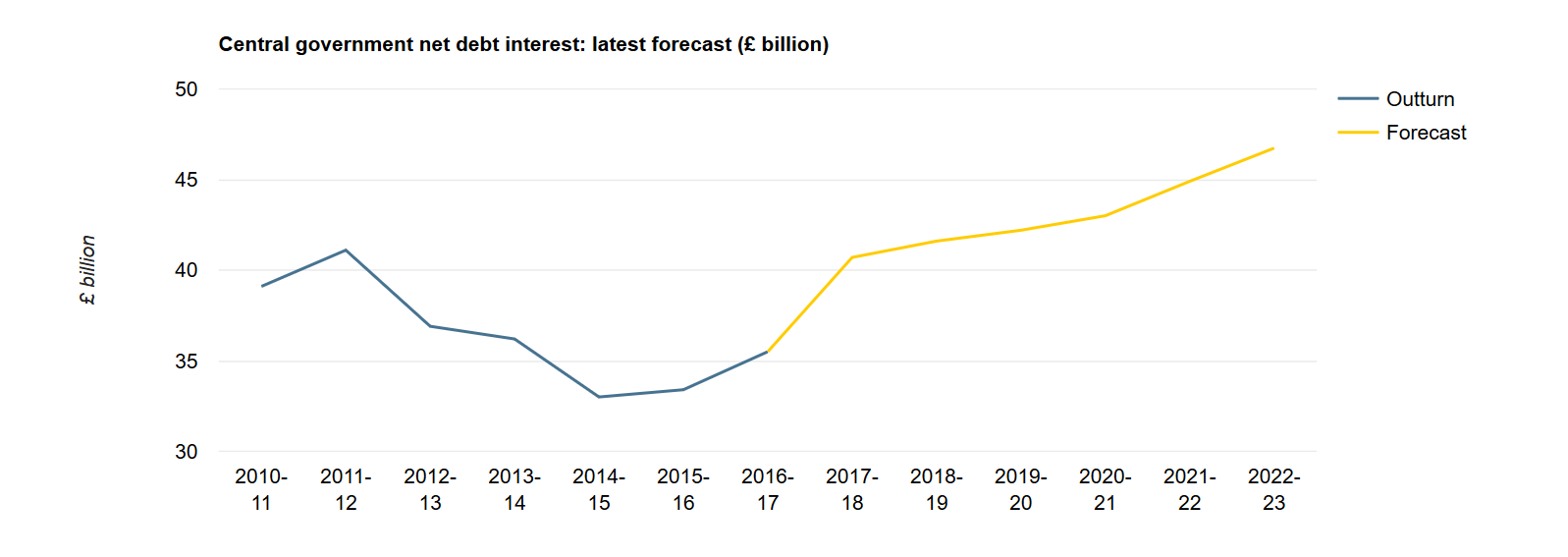

Now, on the impact of rising interest rates and bond yields. A lot of government borrowing is long term (10-year and 30-year bonds being the most popular) so the impact of rising bond yields won’t be felt immediately.

What impacts the total interest payments

• UK conventional gilt rates

• Inflation rate impacting the index-linked gilt rates

• Level of current borrowing

• Level of new borrowing

On an average, around 7% of the total debt is rolled over for UK every year plus new borrowing is made.

A 1% (100 basis points) rise in yields would increase the total interest cost on existing borrowings by 5.1% for the UK in the first year. Those numbers would be compounded in subsequent years.

The stock of index-linked gilts is expected to rise from 16.5% from 2017 to 20.4% in 2022 of total gross public-sector debt. This means that 5.1% increase could be 7.2% for every 1% increase in inflation.

Here is the chart of official debt interest payment forecasts,

Impact of QE

Since late 2012-13, excess cash held in the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF) – QE in simpler words has been transferred to the UK Government on an ongoing basis.

Transfers up to the level of the Bank’s income in the previous year are currently treated as dividends, reducing net borrowing; beyond that, they are financial transactions, reducing the net cash requirement but not borrowing. Any payments made from the Government Exchequer to the APF are also currently treated as capital grants, increasing net borrowing but not affecting the current budget.