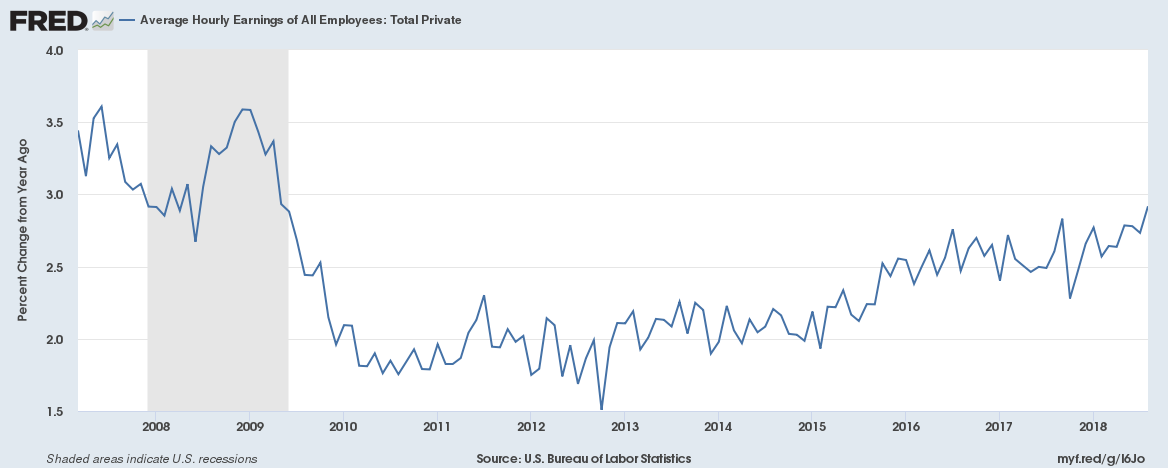

Both the United Kingdom and the United States currently have record multi-year high levels of employment, yet wages haven’t kept up with inflation for the vast majority of people causing a real income squeeze. Although the U.S. recently reported the highest wage growth since the last recession most people don’t feel their wages are keeping up with rising prices. What is going on?

Many economists refer to the Phillips Curve (named after William Phillips), a single-equation econometric model that suggests that as employment levels rise, wage increases follow. But this time it is different. Here are some reasons why wage rises have remained subdued this century.

Decline in Union membership

Union membership has drastically declined this century which has reduced collective bargaining power. Further, fewer new generation job sectors even have a concept of unions.

Sluggish Productivity

The productivity of the economy which is the amount of economic wealth we produce for every hour we work has been lower this century then it was in the last four decades of the last century. Corporates haven’t really invested in new machinery and technology given the financial crisis which in turn has caused lower output.

Workers have become less likely to move to a different location or to a different job for a better wage

Call it the comfort zone or not wanting to leave a settled lifestyle or perhaps fear of the unknown. A recent survey showed that 78% of employees surveyed in the United States would stick to their job if they had flexible working conditions (like the opportunity to work from home) even if their employer didn’t give them a wage rise.

Fewer start-ups and lesser competition

Despite what we hear on people leaving their careers to start up something of their own, the fact is that at least in the United States there are far fewer new start-ups in the 2000’s and 2010’s than there were in the 1980’s and 1990’s. Big businesses have become so big and powerful that they are pretty much buying out any new competition.

Automation

There is no denying that corporations try to automate as many processes as they can to save labour costs. Technological changes have likely put downward pressure on wages.

Wage increases are being replaced or substituted by other things

Workplace pensions have been mandatory in the United Kingdom for the past 3 years. Two years ago, corporations didn’t have to contribute anything towards employee pensions. By April next year that number will be 5% of the employee wage on top of paying the employee their regular wage. (Related: The looming pension crisis)

Likewise, in the United States employers are paying far higher premiums for healthcare. The cost to employers is rising and that is probably resulting in lesser direct wage increases.

The gender pay gap debate

In the United Kingdom, employers with 250 or more employees must publish figures comparing men and women’s average pay across the organisation. What has this caused? Well, the BBC for instance has been cutting pay for men so that their pay is closer to women.

Elsewhere, some organizations have pledged to hire more woman in senior roles to balance out average pay or have pledged to hire more women as a minimum percentage of all employees. A biased employment target would only result in wages getting supressed because the message being sent out is that merit and hard work don’t matter.

On that note, wages for women have increased at a far quicker pace than men in both the United States and the United Kingdom since the last financial crisis.

Related:

Unemployment in Europe is lowest since 2008 but is still twice that of the United States