The IMF, OECD and many economists believe that the world is in a phase of synchronised global growth, a time when economies globally grow simultaneously.

Synchronised global growth would mean that the vast majority of people feel or get richer, global trade grows, and economic imbalances reduce. There is just one problem though – every period of synchronised growth has been followed by a financial shock. The Asian crisis in 1997, the dot com bubble in 2000-2001 and the sub-prime crisis of 2008-2009 all followed periods of synchronised global growth.

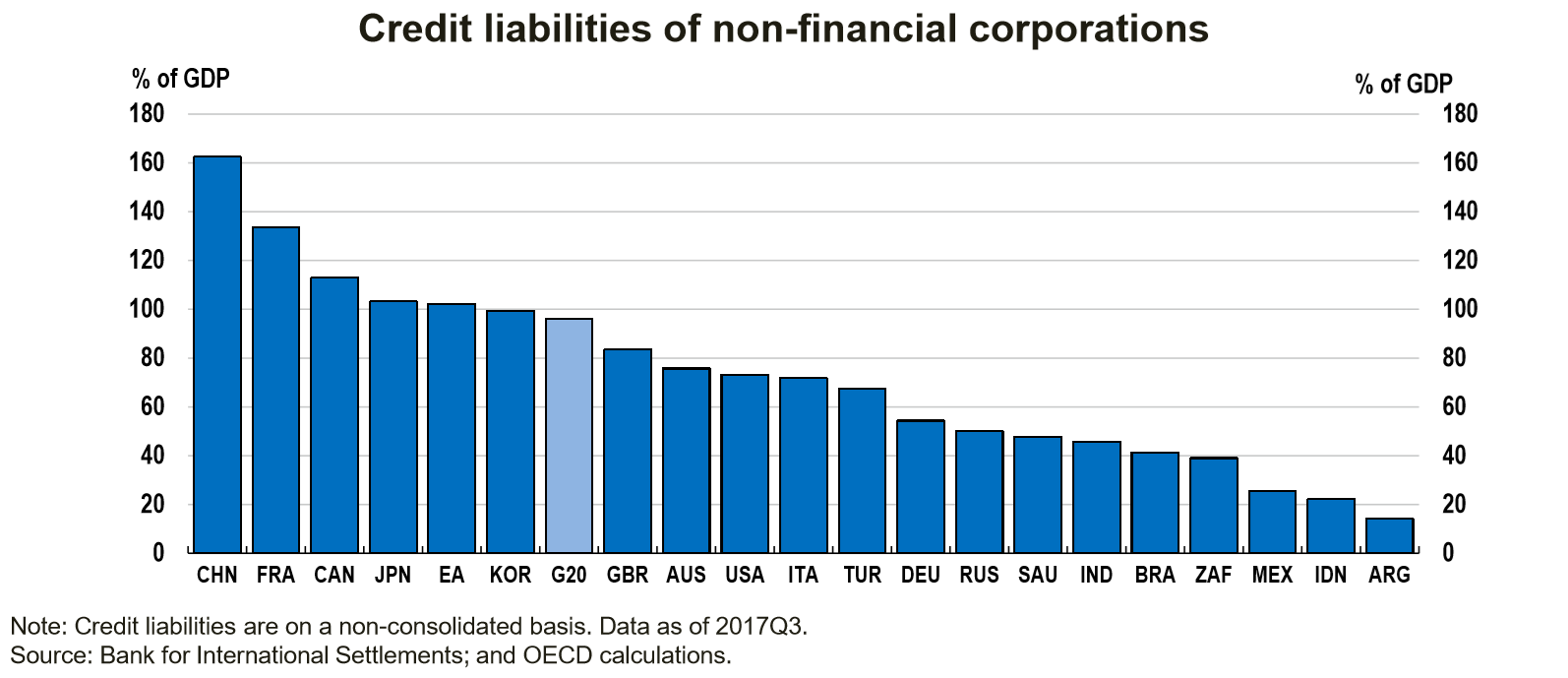

Concurrent economic expansion often leads to increased economic confidence and often excessive optimism causing individuals, corporations and governments to borrow more. Global debt has generally increased during phases of synchronised global growth.

But debt is just one part of it; commodity prices have always increased during such periods and unemployment has fallen causing a labour market squeeze like the we are seeing.

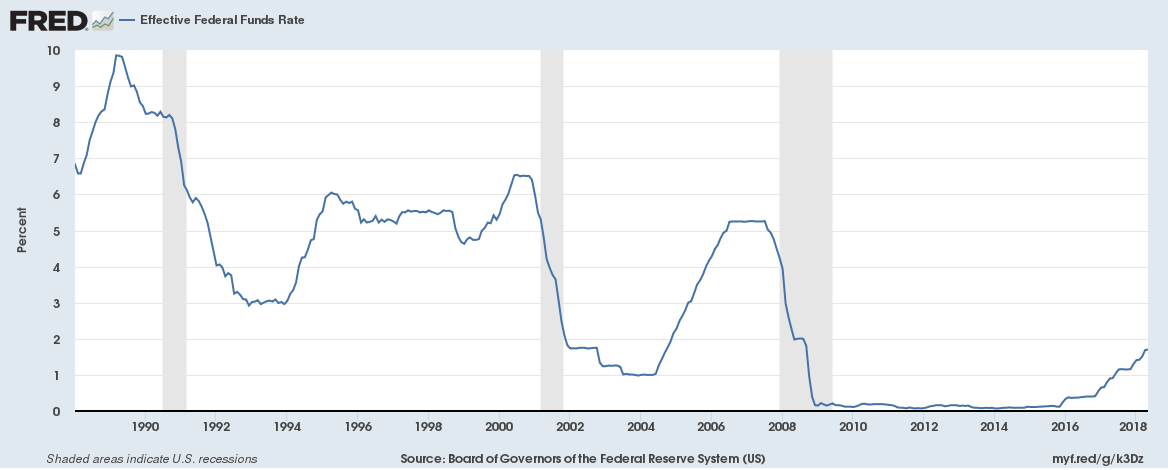

There are other parts to it as well, interest rates in the United States have always risen in a period of synchronised global growth, much like it has now. But once growth starts to fall, U.S. interest rates fall rather quickly.

If synchronised global growth reverses

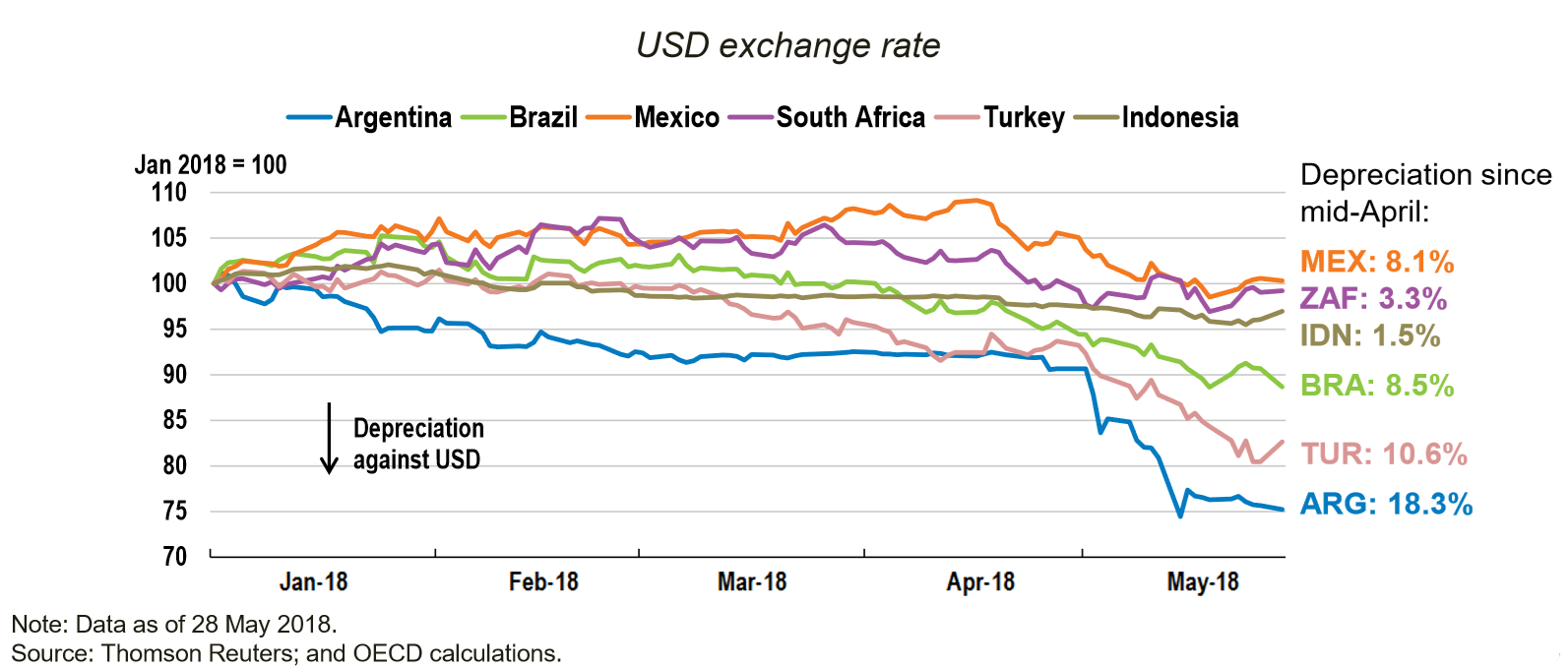

Several things could happen, firstly, investors run away from risk, particularly emerging markets. We are already seeing a bit of that. Global growth would reduce albeit not like in the case of a recession.

With little scope for interest rates to fall any further, central banks might resort to increased quantitative-easing (QE).

Or interest rates might continue to rise to tame inflation brought by synchronised global growth. We are already seeing increased commodity prices and a buoyant labour market in places like the US.

To conclude, synchronised global growth changes the balance of debt, commodity prices and interest rates and brings major financial risks. Synchronised global growth might not necessarily be a good thing.