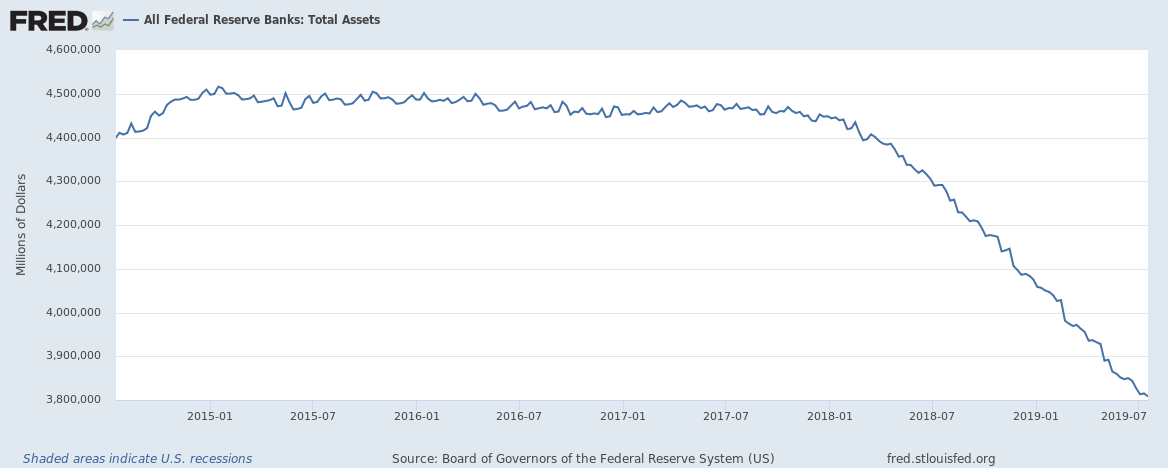

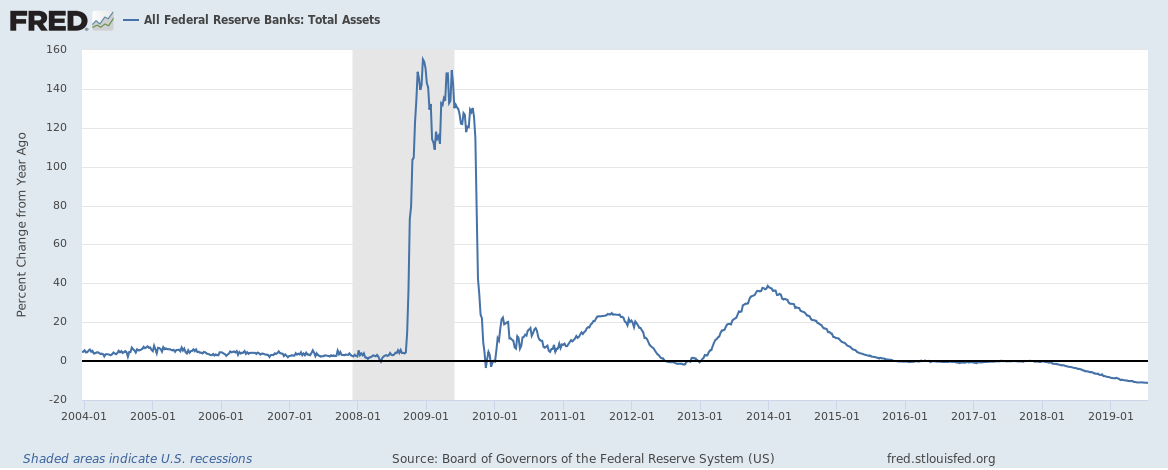

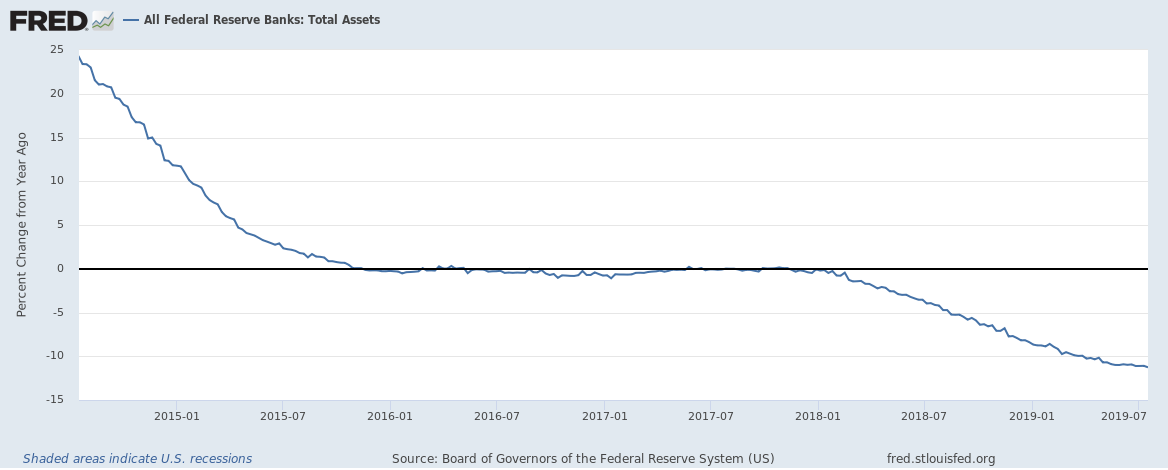

The Federal Reserve has unwound its balance sheet by 12% over the past year and reduced it to $3.81 trillion (from a peak of $4.5 trillion in 2017).

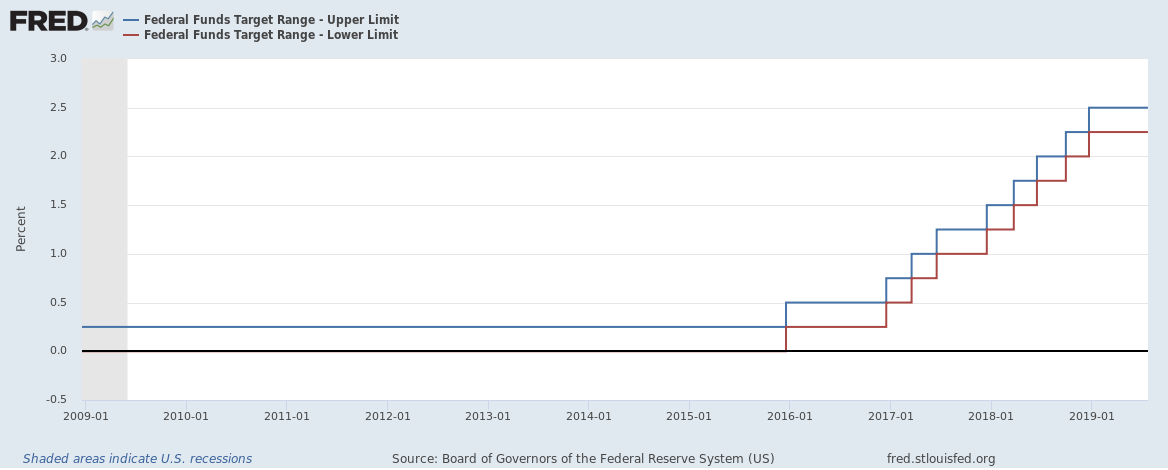

It has also increased interest rates since from 0.25% (range of 0% to 0.25%) in 2016 to 2.5% (range of 2.25% to 2.5%) now.

Why change course now?

Conventional economics would suggest that the Federal Reserve should continue course on reducing its balance sheet and increasing interest rates but … we live in exceptional times.

The U.S. economy by most measures is thriving.

The U.S. has,

- Multi decade low unemployment

- Strong job growth (faster than any time since the financial crisis)

- More job openings than unemployed people

- Continued strong consumer spending

- Buoyant stock markets at all-time highs

- Inflation at target levels

- A strong housing market

- Strong GDP growth of around 3%

But the U.S. also has,

- An increasing fiscal deficit

- Ever increasing government debt

- Falling tax receipt growth

- An ongoing trade war(s)

The economy is thriving. But these are exceptional times. The global economy is slowing and that will affect the U.S. economy.

An interest rate cut before time?

Technically, the economy is so strong now that interest rates should not be cut. Cutting interest rates are the main firepower in the arsenal of any central bank should an economic downturn hit. It is too early for an interest rate cut now but does the Federal Reserve know something that others don’t?

Some would argue that lower interest rates mean lower yields and cheaper credit for both the government and consumers. This is true specially for the U.S. government.

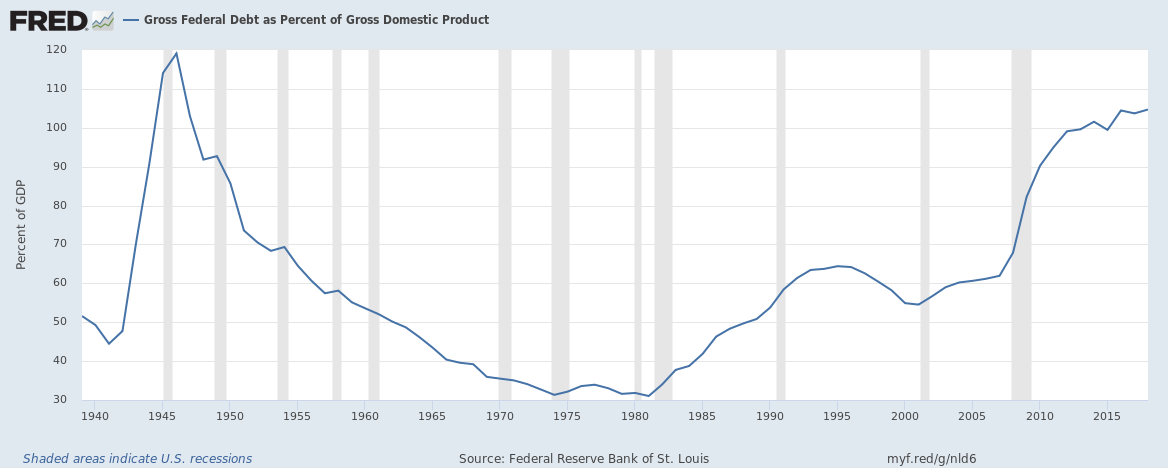

Gross U.S. Federal Debt as percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) hit 105% in 2018, the highest since 1946 and the Federal Government fiscal deficit as percent of GDP was 3.8%. Lower interest rates and falling yields will help.

Stopping the unwind

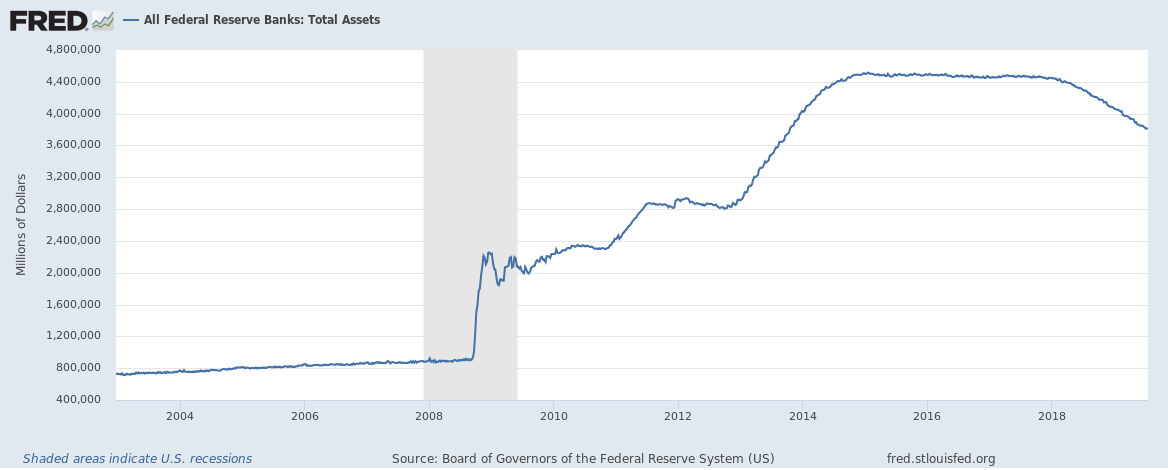

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet swelled from $900 billion at the start of 2008 to a peak of $4.5 trillion in 2017.

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet consists of assets and liabilities. Its principal assets are the securities that it holds in its portfolio, which consist primarily of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. Its principal liabilities include U.S. currency and the reserve deposits that banks and other depository institutions hold with it.

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet became much more complicated during and after the financial crisis as the it acted to provide liquidity to the financial system during the crisis, and to encourage recovery from the recession that followed. To achieve this the Federal Reserve purchased large amounts of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. It paid for those purchases by adding funds to reserve deposits.

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet expansion was one strategy to assist economic recovery. Another was keeping interest rates at or near zero for almost a decade. Interest rates are being gradually increased to “normalize” them.

When Treasury securities reach their maturity date, they are paid off by the government. Mortgage-backed securities are paid off by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Federal Reserve had been going out in the market and replacing those securities with purchases of other securities to keep the balance sheet constant. Unwinding the balance sheet is simply stopping the replacement of securities that mature. The process of unwinding is slow and gradual.

The Federal Reserve is taking a capped and controlled approach to unwinding its balance sheet by letting Treasury securities “run off” at about $6 billion a month and letting mortgage-backed securities run off at about $4 billion a month. That number is going to increase every three months until there’s a maximum of $30 billion a month in Treasuries running off, and $20 billion a month in mortgage-backed securities running off. All this simply means increasing the supply on the market of U.S. Treasuries letting the private sector buy more of them. Hardly takes much to stop the balance sheet unwind, takes even lesser effort to slow the unwinding.

An interest rate cut next week?

Like we have said before, an interest rate cut next week is highly likely but by no means certain. A cut is a definite indicator that the U.S. has reached peak growth at least for now.